Feature

MethaneSat will remind the oil and gas sector “to get back to work”

Measuring methane concentrations as low as three parts per billion, MethaneSat will hold oil and gas firms accountable for emissions. Eve Thomas reports.

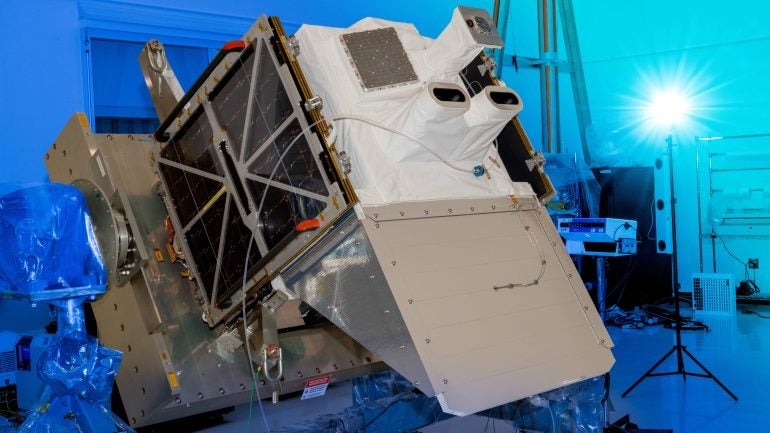

MethaneSat provides data on methane emissions for over 80% of oil and gas operations. Credit: BAE systems

MethaneSat, a satellite measuring global methane emissions from the oil and gas sector, was launched onboard SpaceX’s Transporter-10 rideshare mission on Monday (4 March).

The satellite will circle the Earth 15 times daily, orbiting every 95 minutes, with a swath width of 200km. It will measure changes in methane concentrations as small as three parts per billion, and provide comprehensive information on emissions for over 80% of global oil and gas operations.

Its launch coincides with a period of significant change in the sector, following the announcement of the Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter at COP28, in which more than 50 companies committed to virtually eliminating methane emissions and routine flaring.

Oil and gas’ methane problem

Methane emissions are estimated to be 86 times more efficient at trapping heat in the atmosphere over a 20-year period compared to carbon dioxide.

According to the World Bank, which leads the Global Flaring and Methane Reduction Partnership (GFMR), the oil and gas sector contributes to 25% of all man-made methane emissions, equivalent to roughly 85 million metric tons a year.

Mark Brownstein, senior vice president of the Energy Transition at Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), which developed MethaneSat, tells us: “Methane from human activity is responsible for close to a third of the warming that our planet is experiencing right now. There is nothing that we can do that will have a more immediate impact in slowing the rate of warming that's pressing down on all of us than reducing methane pollution.”

Methane can be leaked into the atmosphere during extraction, production, transportation or storage of oil and natural gas. It can happen as a result of insufficient mitigation, equipment malfunction or pipeline integrity issues.

Considering the example of the NordStream pipeline leak in September 2022, GlobalData analyst Paul Hasselbrinck explains: “NordStream, the once flagship gas pipeline project that was meant to achieve a combined 110 billion cubic feet transport capacity from Russia to Europe, suffered a leak in September 2022.

“The leak was believed to be the result of powerful explosions amid the Russia-Ukraine war and tensions with European counterparts but remains yet unresolved. Updated estimates indicate a leak of up to half a million tons of methane. That is equivalent to 17 million tons of CO2, which assuming a carbon price of $40 per ton, values the societal cost of the leak at 0.68 billion US dollars.”

Solar array installation and environmental testing done by Ball Aerospace. Credit: BAE Systems

Why does MethaneSat matter?

Built in Colardo by the Space & Mission Systems unit of BAE Systems and Blue Canyon Technologies, MethaneSat’s significance lies in its potential to change accountability in the oil and gas sector.

Brownstein explains that the data collated by the satellite is not about “naming and shaming” but a constant reminder to laggards to start pulling their weight.

“When I talk about accountability, I often remind folks that the student that goes to class does all the readings doesn't fear a final exam because they've been doing all the work and the exam becomes the opportunity for them to demonstrate their mastery of the material,” he says.

“The student that spends all their time in the coffee houses and bars, on the other hand, is nervous because he knows that he's not been keeping up. We look at MethaneSat as an opportunity for the good students in the industry to gain validation for the work that they've been doing, while using the information from MethaneSat to prod those that would linger in the bar to get back to work.”

The satellite will create a high-resolution emissions heatmap of area sources, and its data will be freely accessible to the public in an effort to provide transparency in the oil and gas sector.

GlobalData analyst Martina Raveni echoes Brownstein’s hope for MethaneSat’s potential to bring accountability to the sector.

“It is crucial to know which countries are emitting the most methane, how it varies across the landscape analyzed, and how we can account for those emissions,” she says. “In this regard, I think that satellite monitoring is the key, and therefore, MethaneSAT has high potential.

“Indeed, by owning accessible and transparent data, better-informed policymaking, international cooperation, and targeted emission reduction efforts can be possible. However, its impact will depend on the accuracy of its measurements, the willingness of industries to take action, and the effectiveness of policies and initiatives.”

What makes MethaneSat different?

Measuring methane emissions can be a time-consuming and expensive process, usually carried out through field inspections, aerial surveys or fixed monitoring stations that provide continuous air monitoring.

Currently, methane leak records have been reliant upon reports made by companies to countries, and concerns have been raised around underreporting.

Brownstein notes: “What we know from all of those field studies that we've done is that there's no substitute for measured emissions. Companies historically have reported their emissions on the basis of engineering calculations and – at least in the United States – we've shown that those engineering calculations serve to underreport emissions by 60%.”

MethaneSat could represent a new frontier in methane measuring, offering global coverage, and identifying specific sources. Understanding where methane is coming from will enable countries to enact commitments made in the Global Methane Pledge, under which over 150 countries committed to a collective goal of reducing global anthropogenic methane emissions by at least 30% by 2030 from 2020 levels.